Cameras capture mohua and other surprises

Introduction

In 2014, scientists from DOC and Lincoln University used hidden cameras to spy on wildlife during an aerial 1080 pest control operation in the Blue Mountains, West Otago. The results were encouraging.A population of endangered yellowhead/mohua cling to existence in the Blue Mountains. The best way to protect the birds, and other natural values in the area, is to control introduced predators: rats, stoats and possums.

The team of scientists set up cameras to record wildlife activity before and after the pest control operation.

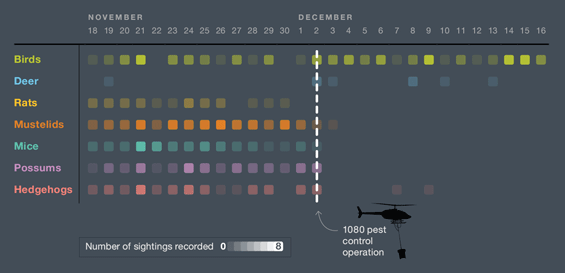

Timeline of camera-based monitoring results

The operation

Tim Sjoberg sets up a motion-sensor infrared camera

Image: DOC

The team studied a 400 ha area within the 7,000 ha beech forest operation zone.

Dr Elaine Murphy explains the team’s approach: “We set up 26 motion-sensor infrared cameras in the forest to monitor the fate of a range of pest species and birds. We had the cameras in place from September to watch population effects before, during and after a National Predator Control Programme operation using 1080.”

Pre-feed cereal pellets were dropped in the operation zone in mid-November. The pellets were non-toxic, allowing pests to get used to them and identify them as a good food source. A couple of weeks later, the toxic 1080 cereal pellets were dropped in the same area.

Both types of pellets also contained deer repellent – the Blue Mountains are popular with fallow deer hunters.

A camera matrix

The team placed 26 wooden tunnels in a grid, 400 m apart on each line and 800 m between lines. Cameras recorded activity around the stations for 30 seconds whenever something came into range.

“The presence of any animal that triggered the camera was classed as a visit, and animals didn’t have to enter the tunnel to be recorded,” says Dr Murphy. “For any bird species, we calculated their abundance in the 28 days before the 1080 operation and in the 28 days following it.”

The fixed cameras operated for a total of nearly 20 weeks. The 1080 drop took place at week 14 and monitoring continued for a further five and a half weeks.

Encouraging outcomes

In total, 4,792 videos of animals were recorded, including flocks of hundreds of finches feeding on the prolific beech seed.

“It’s amazing what activity can be recorded on a camera that we don’t pick up using conventional tracking tunnels,” says Dr Murphy. “Stoats and rats were regularly recorded on cameras, but rats were almost always alone, and stoats were twice recorded in family groups of up to six animals. Stoats regularly visited and entered tunnels even after the meat bait had been removed.”

Results from camera monitoring show the effectiveness of 1080 pest control

The number of cameras recording stoats, rats, mice and hedgehogs was significantly different in the period before the operation than the period after the operation. The cameras showed an immediate drop in pest abundance. No stoats or rats were recorded the day after the operation or within the 38 days after the operation when the camera trial ended.

The statistics showed no evidence of reduced bird abundance in the four weeks after the aerial 1080 operation.

Yellowhead/Mohua numbers up

Mohua were specifically monitored by conventional methods in the study area. The mohua counts before the aerial 1080 operation suggested a decline in mohua numbers from the year before. By contrast, the count after the aerial 1080 operation was the highest since counts began in 2007.

Deer numbers steady

For the hunters, the good news was the apparent negligible impact of 1080 baits on the susceptible fallow deer population. That’s the deer repellent at work.

Hedgehog surprise

“We didn’t expect to find hedgehogs throughout the beech forest, as they’re generally thought of as being less numerous in the higher country,” says Dr Murphy. “In the past, hedgehog control has been largely undertaken by trapping and it was not known until the present study that aerial 1080 could be such an effective control method.”

Clear evidence

“We were amazed at the clarity of the monitoring outcome,” says Dr Murphy. “Our usual methods tell the same story but not quite so precisely. Using cameras to monitor a pest control operation reinforced the value of aerial 1080 pest control for protecting our threatened species.”

Complementary conventional monitoring methods

The initial setup cost for cameras, security cases and locks is substantial. It’s not possible to directly compare the effectiveness of motion-sensor cameras with tracking tunnels due to the huge difference in effort between methods. But the results do complement each other.

- Using conventional methods, the tracking rate before the operation was 10% of sites for rats, and 38% of sites for mice. About two weeks after the 1080 operation, both dropped to 0%.

- Three mustelid lines had tracking rates of 37% of sites before the control operation, also dropping to 0% after the operation.

Predator Free 2050

As New Zealand makes progress toward becoming predator free by 2050, and as powerful field cameras become readily available, more camera analysis will be possible. Rather than the demise of pests, those cameras will record growing native bird populations thriving in our forests.

Scientists

- Peter Dilks, Threats Advisor Christchurch, DOC

- Elaine Murphy, Principal Scientist, Threats, DOC

- Tim Sjoberg, Lincoln University