Archived content: This media release was accurate on the date of publication.

Date: 22 April 2015

Latest field monitoring results indicate DOC’s recent large-scale pest control programme has succesfully knocked back rats and stoats and helped protect vulnerable native species across large areas of South Island beech forest this summer.

Over the last eight months DOC has treated more than 600,000 hectares of priority conservation areas using aerial 1080 to control rats, possums and stoats as part of its coordinated Battle for our Birds programme.

Poison bait stations and expanded trapping networks were also employed to combat the rising predator numbers fuelled by a once-in-15-year beech seeding event.

Mōhua/yellowhead

DOC Deputy Director-General Conservation Services Mike Slater said tracking rates indicate rats and stoats were knocked down to undetectable or very low levels at most sites giving much needed protection to vulnerable native birds and bats.

“Rat levels crashed in most areas and tracking indicates we’ve also knocked back the stoat plague that often follows these beech mast events.”

“It’ll take another breeding season to assess the full impacts but we’re already starting to see positive breeding results for some of the native birds and bats we’re watching closely.

“Early results show the nesting success of rock wren, mōhua, robin and riflemen was significantly higher in areas treated with aerial 1080 than those without.”

For example, rock wren nesting success in the Kahurangi aerial 1080 area was 85% compared to 30% in nearby areas without pest control, said Mike Slater.

“Whio/blue duck and bats also look to have benefitted although we don’t yet have the final results from these monitoring programmes.”

Mike Slater said some native birds had also been lost to 1080 through the pest control operations, including four out of 48 kea tracked at sites in South Westland, Kahurangi National Park, Arthur’s Pass National Park and at Lake Rotoiti.

“It’s unfortunate to lose any kea but without protection most kea chicks are killed by stoats so the overall benefits of these operations outweigh individual losses.”

Mike Slater said rat populations reached extreme levels at some sites and there were lower knock down rates than expected in a small number of operations although rat numbers still plummeted.

“We are closely analysing results so we can pinpoint the factors such as timing and sowing rates that we could improve in future predator plague responses.”

DOC is planning to carry out aerial 1080 pest control over about 250,000 hectares this year – about 50,000 hectares more than normal – to protect vulnerable native species from pests, said Mike Slater.

“We are not expecting another beech mast this year but the Battle for our Birds continues and DOC is committed to extending our regular pest control work to protect our most at-risk native animals and plants.”

Background information

- DOC’s 2014/15 Battle for our Birds pest control programme was targeted to combat a seed-fuelled plague of rodents and stoats across large areas of South Island beech forests. Operations were designed to protect at-risk populations of mōhua/yellowhead, kākāriki/parakeet, kiwi, whio/blue duck, kea, kākā, rock wren, giant land snails and native bats.

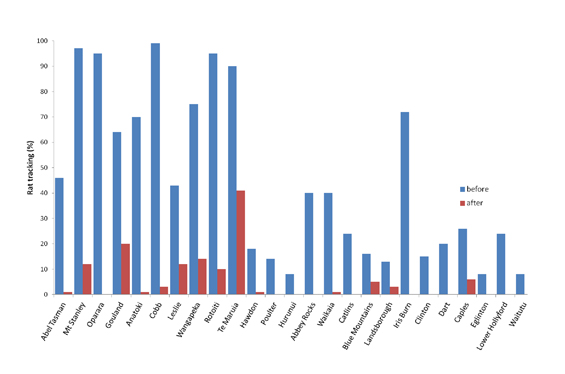

- DOC monitors rat numbers using tracking tunnels before and after pest control operations to show their success and results are shown in the graph below.

- Stoats are only monitored once a year after they breed in the summer. Results from stoat tracking show stoat plagues were prevented at all 15 sites analysed to date.

- DOC is continuing to closely monitor key at-risk native bird and bat species (mōhua, whio, long-tailed bats, rock wren and kea) at a number of sites to gauge the on-going effects of pest control.

Further information

How are the pest control operations judged a success?

Results from tracking rats before and after 25 Battle for our Birds aerial 1080 operations show that rat populations crashed following pest control. Even at sites where rat populations had exploded to extreme levels, there was a significant rat kill.

In addition, results from stoat tracking at 15 sites analysed to date confirm a stoat plague has been prevented at all these sites. Preventing high numbers of rats and stoats protects native bird and bat populations especially when they are breeding over spring and summer and are most vulnerable to attack.

How do you know that native birds benefitted?

DOC is closely monitoring key at-risk native bird and bat species (mōhua, whio, long-tailed bats, rock wren and kea) at a number of sites to gauge the effects of pest control on their survival and breeding success. This work will continue through next summer to assess the ongoing effects of pest control, in particular of stoat suppression over an extended period of time.

Early results from this monitoring programme are summarised below:

Rock wren

In the Grange Range and Lake Aorere areas of Kahurangi National Park 85% of rock wren nests were successful compared to 30% in nearby areas that didn’t have pest control. In these non-treated areas up to one third of adult females also went missing – probably preyed on by stoats. Results from other comparision sites without pest control in South Westland (Haast Range) and Fiordland (Lake Roe) were also poor with nesting success17% and 20%, respectively.

Mōhua/yellowhead

Close to 100% of mōhua nests monitored in the Dart and Routeburn valleys produced chicks and 97% of adults survived. All key mōhua populations received pest control last year so there were no non-treated areas monitored. However, previously nesting success without pest control in the Dart was 47% (2006).

Kea

Monitoring showed that nesting success of a small sample of kea was variable. Three broods laid prior to 1080 operations failed due to being preyed on by rats. No nests were detected for monitoring in the main study site in Kahurangi after pest control but in another site in the Hawdon valley in Arthur’s Pass National Park both nests monitored were successful, due to combined trapping and aerial 1080 control. However, the main focus for monitoring kea will be next spring when the effects of reduced stoat numbers should show in their breeding activity.

Robin and riflemen

Robins were monitored at Mount Stanley in the Marlborough Sounds with nesting success of 50% registered in the treated area compared to 7% in the untreated area. Riflemen were also monitored at Mount Stanley where 100% of nests produced chicks in the pest control area compared to 29% in an area not treated with 1080.

Whio/blue duck

Whio/blue duck are being closely monitored in the Wangapeka valley in Kahurangi National Park where the most productive breeding in 11 years has been recorded (36 fledglings between 16 adult pairs). Aerial 1080 treatment and stoat trapping at this whio security site has helped to protect the birds from stoats.

Long-tailed bats

DOC is closely monitoring long-tailed bats in three pest control areas but results won’t be available until next summer. However, results from long-term monitoring in the Eglinton valley show long-tailed bat numbers have increased four-fold over the last 15 years due to sustained pest control using a mix of traps, poison bait stations and aerial 1080.

Short-tailed bats

The short-tailed bat population in the Eglinton also appears healthy with a record number of 1731 bats emerging from a single roost tree this past summer. Results of monitoring before and after the aerial 1080 operation showed 99% survival of this species.

What about the rock wren that went missing last spring?

There is still no clear evidence as to why 22 rock wren being monitored in Kahurangi National Park went missing after unseasonable weather and snow and the pest control operation last spring. While some birds were probably lost to 1080, early counts indicate the high nesting success due to stoat control has already balanced this out with 61 birds estimated in the area after the operation was carried out compared with 49 birds before hand. The full effects of aerial 1080 pest control on rock wren won’t be known until the end of next summer when the birds have another chance of breeding with reduced stoat numbers.

Why was the rat knock-down lower in some areas?

The seed-fuelled mast conditions prompted extreme rat population levels at some sites – levels that DOC had not attempted to control before. DOC is still closely analysing results from each operation to determine the factors that might have affected its effectiveness at killing rats. These factors include rat population levels, timing of operations, sowing rates and the effect of exclusion areas. The lessons learnt from last year’s beech mast response campaign will help improve predator plague responses in the future.

What about the stoat results?

Stoats are not monitored as frequently as rats and mice because they only breed once a year and therefore their numbers do not rise in the same way that rodents do.

Results from stoat tracking at 15 Battle for our Birds sites after summer breeding showed no evidence of stoat plagues. Results showed that 13 sites had very low stoat tracking of less than 10%; the other two sites showed tracking of more than 10% but still at considerably lower than plague levels. At six of these sites trapping contributed to the pest control effort.

Will Battle for our Birds continue?

Assessment of beech trees in a number of South Island areas shows no evidence of seeding this autumn. With no beech mast in sight, there will be no need for a repeat of last year’s major coordinated pest control effort to combat associated predator plagues. However, DOC will continue its regular pest control work under the Battle for our Birds banner.

DOC is planning to carry out aerial 1080 pest control over about 250,000 hectares this year about 100,000 hectares more than normal – to protect vulnerable native species from pests. This is an extension of DOC's regular pest control work to protect the most at-risk native animals and plants. Ground control methods such as poison bait stations and traps will also be used as key components of this programme.

Contact

Fiona Oliphant, DOC media advisor

Phone: +64 3 371 3743 or +64 27 470 1378